Thank you for your interest in Canada

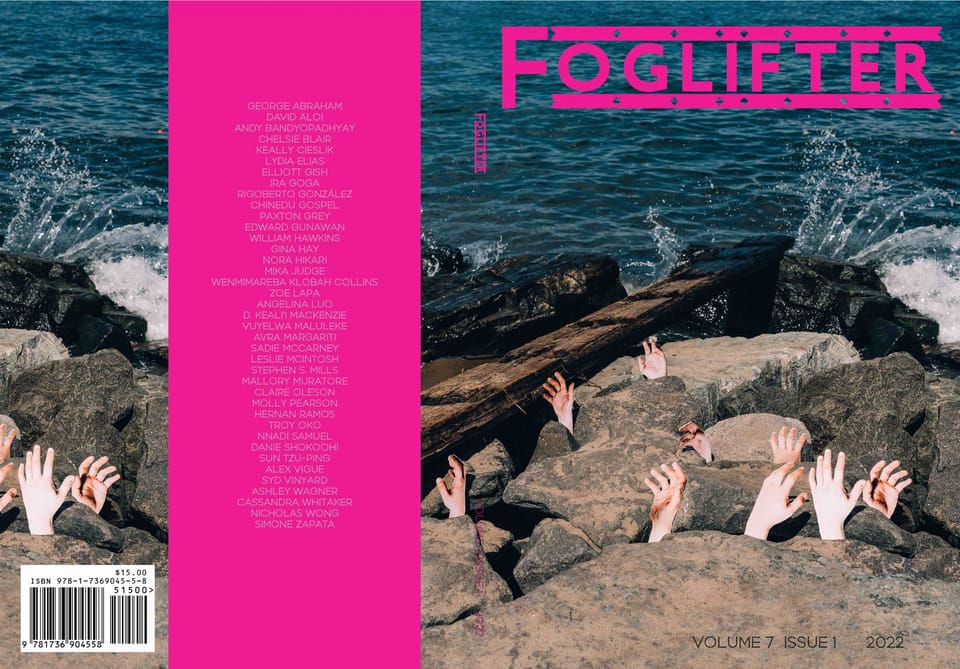

This piece was originally published in print, in the literary journal Foglifter, volume 7, 2022.

From: donotreply@cic.gc.ca

Date: Thursday, May 12 2022 at 11:45 AM EST

Subject: We are waiting to hear from you!

You are?!?!?!

We applied for permanent residency 15 months ago. I submitted my fingerprints, my blood, my urine. My trans, queer body. Please, please let me seek solace on your soil. Please don’t make me stay here. Please don’t keep me here, witnessing.

We need something from you to continue processing your application.

Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) needs updated police reports. They want to make sure we haven’t been arrested since the last reports, 21 months ago. We stayed away as our friends marched in protest after protest. We haven’t been arrested because we can’t afford to be.

My husband Raj and I haul ass to the post office on Saturday morning. The lady at the window looks at my hands.

“You sweat a lot?” I nod. “We can’t read the print. Wipe those fingers down. Try again.”

Fifteen minutes later:

From: Criminal Justice Information Services <edo@services.fbi.gov>

Date: Saturday, May 14 2022 at 11:06 AM EST

Subject: Identity History Summary Request

Your Identity History Summary Response is now available for review. You can review your response by accessing the secure link and PIN found in the original e-mail previously sent to you. This response is available for 90 days.

I download and file our reports 51 hours after Canada asked for them. At home with Raj, my palms are dry.

***

Raj landed at the George Bush Intercontinental Airport at age 22 after a twenty-four-hour journey from Mumbai. He came to America for a PhD program in computer science. He came to America to escape his parents. He came to America to learn Chinese and tango and salsa. He came to America to say a big fuck you to the pressure to become an engineer. I loved him from the day I met him.

When we were first dating, Raj was on a student visa, a temporary permit. I feared our immigration statuses would tear us apart after graduation. In 2010, when we got married, I used my American citizenship to sponsor his green card and felt a deep relief. A year later, we sealed our vows in India, and Raj sponsored my Overseas Citizen of India card. Again, I was relieved—if we ever needed to live and work in India to take care of family, we could be there, together.

All this paperwork was possible because I was legally female at the time—a bisexual queer, an egg in waiting, a person who had no idea I was trans, a wife with a husband.

I was lucky to discover my inner gay man in 2016 and to begin medical and legal transition in 2017.

If my husband and I had met 40 years earlier, our union would’ve been illegal because we committed the crime of marrying someone of a different race in America.

If I were 20 years younger, my parents would be under investigation for child abuse because they committed the crime of supporting their trans child in Texas.

If I had started testosterone and had top surgery and changed my legal sex 15 years earlier, our sleeping together would’ve been illegal because we committed the crime of homosexual activity in Texas.

If I had transitioned 7 years earlier, our union would’ve been illegal because we committed the crime of marrying someone of the same sex in America.

If I had transitioned 7 years earlier, our Indian marriage would’ve been illegal, and we could’ve been arrested for having sex in India.

Welcome to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code—a statute that criminalized sex “against the order of nature.” It always made me chuckle—have you not seen nature? In 2006, a fabulous Rajasthani prince came out with a Pride flag and a big fuck you to the law. Rajasthan is the state that erupted in protest in 2008 because the movie Jodhaa Akbar dared to show a straight Hindu-Muslim couple in love. Queer activists and lawyers and writers—and yes, the fabulous prince, too—organized in the face of massive prejudice, and in 2009, the Delhi High Court overturned Section 377. Four years of freedom, then in 2013, the Indian Supreme Court said Delhi had it wrong and queer sex was outlawed again. In 2018, after even more organizing by India’s queers, the Indian Supreme Court had a change of heart and struck down Section 377 for good. The rationale: everyone has a right to privacy. Gay marriage and gay adoption remain illegal.

Today, we can’t get arrested for having sex in India, but we are breaking the law if we try to get married. Is our marriage still legal, given that I was female when we signed the papers? No one knows.

Given this ambiguity, we approached my transition gingerly.

After my voice deepened and I grew facial hair, every time we went back to India, I altered my pitch, shaved my beard, and put on feminine drag. I changed my legal name to Andy rather than Andrew so that, if Indian immigration asked, I could pretend it was short for Andrea, just a normal wife, nothing to see here, please let me in to see my family. I felt like a saboteur sneaking through customs with an F on my American passport and my Overseas Citizen of India card.

In 2018, draft memos suggested legal transition may become impossible for federal documents in the United States. I was running out of time.

I changed my gender marker to M on my passport, my social security card, my driver’s license, my birth certificate. I knew this might mean the end of my marriage in India, legally speaking, and with it, the end of my Indian permanent residency.

Still, it was worth a try. Raj and I went to the consulate together and asked to change the gender on my Overseas Citizen of India card. Clerks didn’t know what to do with us, and we reached out to queer lawyers in Mumbai.

“Do you want to be a Supreme Court test case?” one asked.

We shook our heads. We didn’t want to be tied up in the Indian courts. We didn’t want to take on the corruption, the tabloids, the harassment. Not under Modi. Not ever.

Instead, we did what desis do: we found an uncle who used to work at the consulate’s visa outsourcing center in San Francisco. His lilting Jamaican-Indian accent and cheerful smile won us over. He was excited to take on the bureaucratic challenges posed by our love.

“I found it!” he said, and attached a new form. “‘Other particulars.’ We are changing ‘other particulars.’”

My gender was an ‘other particular,’ like a birthmark. We filed the paperwork without incident.

***

I want to tell you about our weddings and receptions: Atlanta, Kolkata, Houston, Mumbai. The first wedding is the real one, the one we designed for ourselves: a small ceremony on the rooftop of our downtown Atlanta loft. We vow to be “nerds together forever,” as witnessed by the secular preacher we hire from Yelp and my parents, grandparents, and Raj’s dad. The next day we host a potluck party with all our friends. My mom makes the cake and Raj’s dad asks my grandma to compare the rules of cricket and baseball. We dance tango on our hardwood floors, our tango teacher beaming in the audience. I am a PhD student and we have a small budget and it is the best.

The Kolkata wedding and the Mumbai reception are for Raj’s parents. Every event is for them to show their neighbors that they’ve made it: their only son made it to America and got a PhD and an engineering job and a wife and a giant house and yes, she is white and also American and has no caste but look, she wears a sari and goes to temple with us and speaks Hindi even and yes, she is learning Bengali too, and she is also getting her PhD, and look, our child is going to be rich, our grandchildren are going to be rich.

The Houston reception is for friends from school, for the community who saw us fall in love in the first place, when I was an anthropology undergrad and Raj was a computer science PhD student dreaming of being a liberal arts major.

By the time we get Raj’s green card we are more married than anyone we know, having affirmed our vows so many times. We settle into a routine of exploring Atlanta by bike while I work on my dissertation and Raj works on his job. I get Raj a camera for his birthday, and he starts taking photos of Atlanta’s freight trains and tracks. I join the Atlanta Women’s Chorus and delight in singing with queer women—it’s a sister chorus to the Atlanta Gay Men’s Chorus. I am bisexual and I am visible and heard.

We immerse ourselves in our shared love of books and indie bookstores and public libraries. Together, we read a lot of immigrant literature. Novels, creative nonfiction, essays. People from all around the world making a life in America amid all the contradictions. Part of this is reflecting on Raj’s experience. Part of it is reflecting on our marriage. And part of it is a simple love of a good story.

After I finish grad school, we move out west to San Francisco, in search of more bicycle infrastructure and more queers and more artists and year-round mild weather. We land in an attic with exposed wooden beams and gleaming hardwood floors in the heart of the Castro. It is here that I start to meet more out trans people, start to feel inklings of my gender shift, start to realize that maybe I need to embody the queer men I see out and about. It is here that Raj starts to meet more artists, starts to take his photography more seriously, starts to realize that maybe he needs to embody the artist full-time.

In 2015, I remove my uterus. I don’t want any more 21-day periods. I don’t want to become pregnant, ever. Most of all, I don’t want the state to force me to carry a child. I am from Texas, and I know that abortion bans are evergreen possibilities.

By mid-2016 I’ve come out to myself and to Raj as a queer man. Through many long talks with each other and friends and therapists we’ve committed to stay together through my transition. That fall, we fly to Sevilla and Marrakech to celebrate. I buy a notebook with Andrew engraved on the front, the first physical manifestation of my new self. On the eve of the American presidential election, we stay up late at our Airbnb with apple cider, ready to celebrate our country’s first ever female president.

As midnight turns to two and then four am, it’s clear that something is deeply wrong. Every pollster had assured us that the country was on a solid, queer-affirming track. And then state after state goes to the man who said he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue without losing votes.

By the time the election is called, Raj and I are spent. Our apple cider remains sealed, our cups empty. We haven’t slept. We make coffee anyway. We briefly consider never returning to San Francisco, finding a way to get a work visa and a tech job outside the United States. We have an extended conversation about my transition: I was just about to come out to friends and family and colleagues. Would I still be able to access medical care under the new administration? Would I still be able to change my papers?

We fly home and the city is devoid of life. We walk the Castro mouths agape, in shock, and eyes down, in grief. As these first waves subside the protests begin, and with them some sense of collective action rises, the will to make it better palpable.

We are in California. The state legislature protects access to trans health care. I come out at work, and my gay CEO celebrates me. I come out at my gym, and my trainer high-fives me and helps me strengthen my pecs. I come out to my parents, and they are shocked that I was worried about their support.

I start testosterone, have top surgery, and change my paperwork while I still can.

Then an armed militia attempts to kidnap and execute Michigan’s governor.

A mob ransacks the capitol and calls for the hanging of the vice president.

“This feels like India,” Raj says. “I did not bust my ass to land in another third-world country.”

A scholar of civil wars around the globe and across history pens a New York Times bestseller explaining that, if you analyze America the way you would analyze “Ukraine or the Ivory Coast or Venezuela,” you see that America is fucked, that America is now in the twilight zone between democracy and autocracy, at high risk for civil war. I send the book to my dad, a political science professor.

Meanwhile, there’s a bill in Missouri to make trans health care illegal for adults.

I cannot go to Missouri.

A draft opinion by Samuel Alito, leaked to Politico, overturns Roe v. Wade by saying women’s right to abortion wasn’t in the constitution.

Trans people weren’t in the constitution, either. At least I had my hysto.

Jamelle Bouie writes an op-ed in the Times about how Obergefell is next after Roe, based on Alito’s logic and the broader logic of the movement that created this court.

I need to stay married to my husband.

I am leaving my country.

***

Not everyone gets it. Some do and make a different choice.

I have lunch at a seaside cafe with a journalist in her fifties. “The sixties and seventies were violent too,” she says. “We’ll make it.”

I gaze at the stars with my writing group. Shelcy is from Haiti. Courtney’s dad is from China. Leticia is from the Philippines. We are in America, the land of opportunity. I have to leave, I tell them. It is a pull in my bones. A scream in my heart that tells me I cannot exist here much longer. A compass pointing the fuck out of here. My writing group recognizes this ache in themselves, in their parents. They are still American, still committed, for now. But they nod, a solemn ode to immigrant intuition.

I walk around Lake Merritt with a tattooed Japanese-American friend. “I am going to build a fortress here,” she says. “A safe house for queer and trans folk. We will stock estrogen.”

I walk along the ocean with a tattooed Bangladeshi-American friend. I am listening to the waves lap the shore, smelling the trees, feeling the mist on my face. The administration has just floated the idea of rendering trans identity documents invalid. If I have no passport, no driver’s license, no social security card, no birth certificate, all because I have changed my gender marker on each one, who am I?

I have to leave before I become a non-person.

My friend bought a house. He’s staying, marrying his boyfriend, having babies. “It’s California,” he says. “It’s somewhat protected.”

I feel a gulf the size of the Pacific between us.

Can’t you see that I’m dying?

***

Canada requires a medical exam to make sure you don’t have a condition that would overly burden their healthcare system. I have anxiety. I wonder if I will be disqualified, even though anxiety affects 40 million American adults.

Lucky for me, I’ve had anxiety all my life, and I’ve developed coping strategies: medication, therapy, and project-managing the shit out of what makes me anxious. Immigrating to a new country is the ultimate opportunity. I brew a coffee and rub my hands together and make a spreadsheet: Immigration Steps - Express Entry. We have 25 steps to complete. We start gathering all our documents in June 2020, aware that in most countries, the permanent residency process takes years from start to finish.

Bring it on.

After getting a third party to certify that our American university degrees have equivalents in Canada, our next stop is to take English tests. The quickest appointment I can find is in three months in Portland, 700 miles from home. COVID is rampant and there aren’t vaccines and we’re not supposed to travel but we have to get out of here. So I book the tests and we mask up and sanitize our hands over and over. I’m not obsessive, just following CDC guidelines.

When we arrive in Portland, wildfire smoke has spiked the air quality index to over 500, temporarily making our escape route the most polluted place in the world, no match for masks. Our Airbnb has no air conditioning and no air filter and we are choking inside, choking outside, choking everywhere. Still, we show up for our International English Language Testing System appointment, and for four hours, we read, write, listen, and speak to show the examiners that we are native speakers, that we will adapt well to life in Canada. I am good at tests. I can do this.

On our application, we list every address we’ve ever had, every job we’ve ever had, every country we’ve ever been to. We get fingerprinted at the post office and get our records from the FBI. We ask a doctor in Chinatown to examine us for fitness for Canada, and she asks us to give blood and urine. We share bank statements to show proof of funds to settle. I get reference letters from every employer I’ve ever had on official letterhead. I attach our marriage certificate and all of our passports and visas and my name change and gender change documentation. Canada requests our biometrics and we get fingerprinted again, this time at an immigration office. I capture every step in my spreadsheet. We’re doing it.

We file our finalized application in February 2021, eight months after starting the process.

I keep checking IRCC’s official website for updates, but the page is stuck on an apology for COVID delays. Not knowing is the worst. So my project manager brain finds another way: immigration news websites, which use freedom of information requests to publish IRCC numbers. My favorite is cicnews.com. I check it every morning with my first sip of coffee.

As of April 29, 2022, there are 32,883 of us in line.

I’m scheduled for bottom surgery in August 2023. I booked it in January 2019, when the wait list was four and a half years long. I hope I’m not living here by then. I wonder if any other surgeons can get me in sooner. My anxiety brain spins up a new spreadsheet: Doctors Who Make Dicks, But Aren’t Actually Dicks.

I tell all my friends to get their passports. I pay the fees for trans folks who can’t afford them. Some progressives tell me about issues north of the border. What, you think Canada is perfect?

I tell them I’ll listen once the United States has free, universal healthcare that covers abortion access, eight months of paid parental leave per parent, and zero laws criminalizing gender-affirming medical care.

One progressive tells me crossing states is the same. “I consider myself an immigrant too,” she says. “I immigrated from Arkansas to New York.”

I am filled with rage.

No, I think. You did not submit your fingerprints and your blood to USCIS. You did not beg the officer to consider your relationship worthy. You did not have to prove that through your education and work experience you were one of the good ones. You did not have to get a stamp to cross the border. You did not have to carry your immigration documents with you everywhere while driving through Arizona, lest a cop ask you to show your papers or risk deportation.

No.

I deeply resent that I have to explain this shit to anyone.

“There is always grief in leaving,” a friend’s mother finally says. “But what the fuck was I supposed to do? Stay in Brazil?”

“I had forty years in America,” she continues. “Then the Buffalo shooting this week, another one. What is the political affiliation of all the shooters? Why isn’t that published in a newspaper, big letters, front page?”

She is searching for her next country, for safety.

And I feel seen.

My own parents text me after the draft opinion on Roe v. Wade leaks: “Any news yet on Canada?”

They are waiting for me to sponsor them, to get them out of their small Texas town. This, too, is part of immigrant anxiety. It is the next spreadsheet: Mom and Dad - Express Entry.

***

“I’m going to sell everything,” I say. “Every last piece of furniture. Everything but our vital documents, clothes, and laptops.”

“What about our bicycles?” Raj says.

“We keep those.”

I’m preparing the ultimate Marie Kondo. I toss with abandon. I enjoy the thud of each item as it lands in the exit pile.

But I cannot Marie Kondo my friends. I cannot Marie Kondo my grief. I cannot Marie Kondo the feeling of singing with the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus, of walking through the New York Public Library, of riding my bicycle in all the American cities I’ve loved.

Still, I want us to land at Toronto-Pearson with a handful of suitcases and big dreams.

***

When we watched The Namesake together, Raj saw the protagonist making chaat out of Rice Krispies. “Now that’s how you do it! Hah!” he said.

Our house will always have chai and chaat.

In our shared future, Raj will be an immigrant twice over, from India to America and then to Canada. I’ll be an immigrant once, moving just one country over, still in the same time zone, the same language. But it’ll be a completely different world from a legal perspective.

Canada is the first time I’m making a permanent move away from my home country, and I find myself inhabiting many tropes of immigrant literature.

You know the stories: Person with grit leaves it all behind for the promise of a better life. Works their ass off in a foreign land, works with dignity even if they are a cab driver in their new country when they were a doctor back home. Gradually masters the language and the slang and the weather and the customs. Decides what to keep and what to toss from home. Has children, and is simultaneously proud and disappointed when their children are indisputably natives of the new country, when their children roll their eyes at having to learn their parents’ language or cooking or traditions. The children have their own identity crises as they grow, and in their coming of age gradually realize that they must integrate their heritage and home.

We celebrate the determination of the protagonist. We do not shame them for leaving their country behind.

Only this literature doesn’t exist for people leaving America.

When Americans go abroad, we call them expats. They’re the colonizers, on a jaunt in a foreign land, a holiday where they marvel at the local customs, but rest assured that they can always go home to the most powerful country in the world, the shining city on a hill, the place everyone else wants to be.

Only applications to come to America have been declining.

We are not used to Americans leaving under duress. We are not used to the idea of our citizens begging other countries to let them in, to allow them to build families and careers and businesses and novels and poems and photographs.

I am leaving America. I am begging Canada to let me in, to let me bring my husband, to build our little writer-photographer-Indian-American family.

I am probably not coming back. I am going to have children with my double-immigrant husband. Our children are going to roll their eyes at us, saying learning Bengali is overrated, saying they don’t need lectures on the broken promises of America and India, on how hard we worked to create a life and a future for them in Canada. They’ll just want to zone out and listen to their music.

They can listen to their music. Raj and I will hold hands in our rocking chairs.

We will turn to my parents. We will turn to our queer and trans friends who made it out. We will call and write and text with our friends and family who stayed behind. We will watch and donate and organize and wait for the day when our bodies are safe in the United States. When gender-affirming healthcare is a legally protected human right for people of all ages in all fifty states. When same-sex marriage is secure not just for now, but for the long haul. When the shootings cease. We also know that day may never come.